by Maria Meindl & Martin Julien

More YOU: Drama study with Miss Marjorie Purvey

By Martin Julien

Every Saturday morning – from the ages of eleven to fifteen – I would open the nondescript metal door at 752A Yonge Street (just south of Bloor, beside the old Uptown theatre) and make my way up the two fights of dusty, worn-linoleum stairs to the tiny stage, waiting area and ancient radio studio that made up The Toronto School of Drama. The director and sole employee was Miss Marjorie Purvey. She mentored the aspirations of hundreds of young student actors between its founding in 1947 until its closure in the early-1980s.

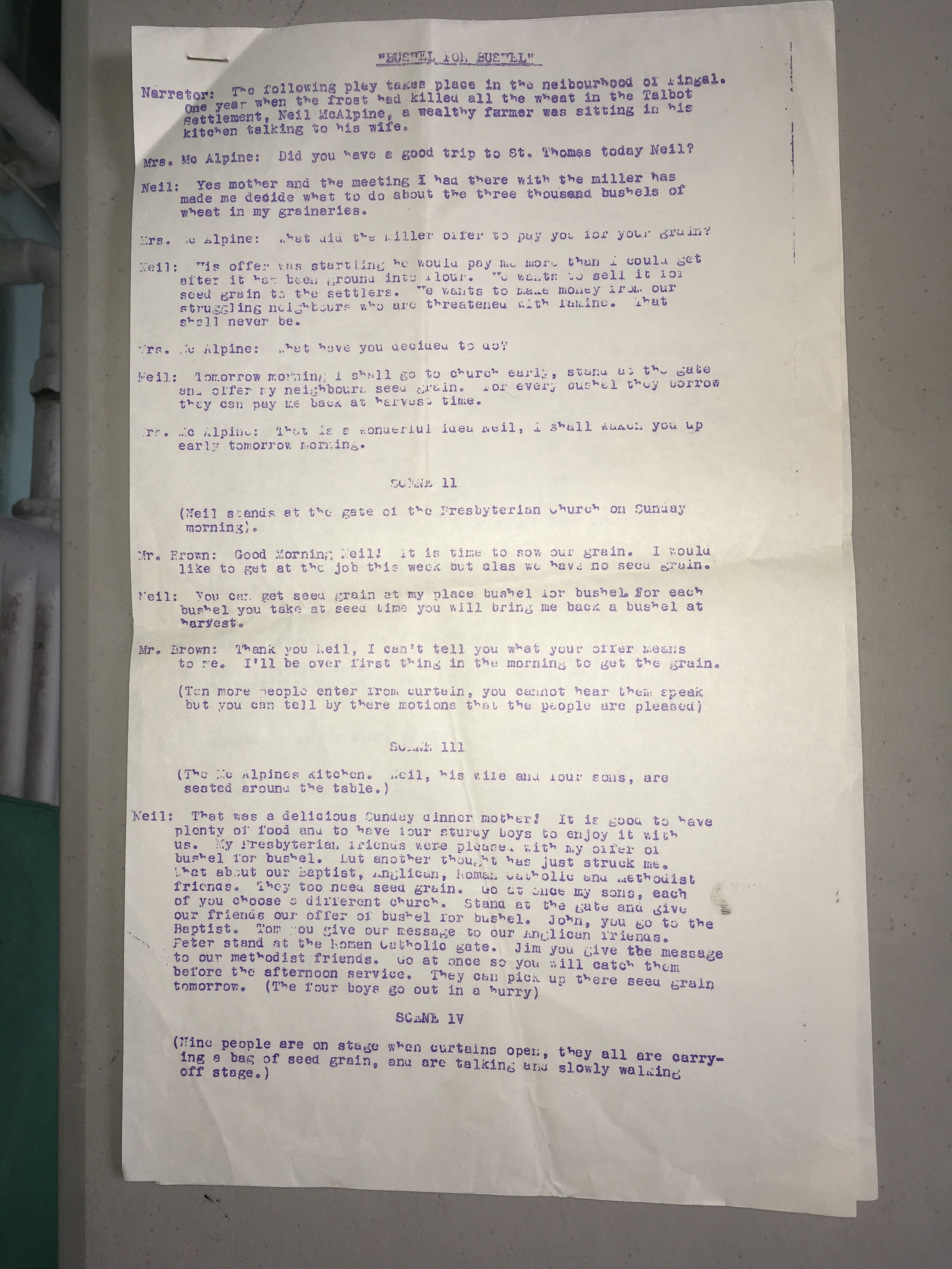

Here we (a class of about ten similarly aged aspiring thespians) would do physical warm-ups, group exercises in imagination and concentration, and then games of improvisation on stage, followed by two-handed scene work from Euro-American realist ‘classic’ plays by the likes of Maxwell Anderson, Eugene O’Neill, and Terrence Rattigan. The last half-hour of the two-hour session was always filled by re-creating characters from the dog-eared foolscap scripts that Miss Purvey had written and typed herself for the Children’s Theatre of the Air radio program Peter and the Dwarf which aired weekly during the late-1940s and ‘50s on local station CKEY. Miss Purvey would sit in the ‘control booth’, contentedly smoking and not-so-contentedly directing us to be bigger, smaller, faster, slower, and always: more YOU – let your personality shine!

We all called her Miss Purvey, though she never divulged a thing about her personal life. Only years later, upon reading her obituary notice of August 10, 1984, in The Globe and Mail did I learn that her married name was listed as Compas, and that she had a son and grandchildren. By the time I studied with her, in the mid-seventies, the ‘glory years’ of her drama school – and of her professional influence – were long over.

She’d begun studying drama and ballet from the age of fourteen, and was a graduate of the London College of Music in the University of West London. She began teaching dancing, and then acting, during the 1930s “[…] where she used her free time to keep children off the streets during the depression” (“Film”). She was an original member of ACTRA in the 1940s, (then called the Radio Artists of Toronto Society, which produced the unfortunate acronym RATS), and by 1945 was also credited as a primary writer for the radio program Curtain Time on CBC’s Toronto flagship station CBL (Chamberlain). In a 1951 Globe and Mail column, influential critic Herbert Whittaker named Purvey as one of the individuals “responsible,” with Leon Major and Celia Franca, for the formation of Young Canada Players at Toronto’s Museum Theatre, a “teenaged group [that] shares the same high purpose of the recently formed Jupiter Theatre” (24).

FRANK CHAMBERLAIN

The Globe and Mail (1936-Current); May 15, 1945; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Globe and Mail

pg. 11

In the 1950s, she was the premier acting instructor for children and teenagers in the city. As child star Rochelle Goldstein Porter puts it: “[m]y teacher, Marjorie Purvey, was the only drama teacher in Toronto during the fifties. Anytime CBC needed kids they went to her, there was no other place to cast children back then” (Goldstein). Lois Maxwell, (James Bond’s future Miss Moneypenny), studied with her; as did Lloyd Bochner and William Shatner, before they decamped to pursue international careers in Stratford and Hollywood. Johnny Washbrook, who played the lead character in CBS’s Western series My Friend Flicka (1956-57), was a student; so was Janet Amos, who began performing with Dora Mavor Moore’s New Play Society at the age of eight, and later became a founding actor at Theatre Passe Muraille and then artistic director of the Blyth Festival (Nothof). Purvey also played the character of Martha Wales in the television series Hawkeye and the Last of the Mohicans (1957).

By the mid-70s, when I studied with her, Miss Purvey seemed as dedicated as ever. What did her teaching look like? It was meticulous and organized, with each class and term trajectory closely calculated. “We try to develop poise and confidence through self-expression and supply a background of culture so necessary in so many walks of life,” she told an interviewer (Haworth). Perhaps this was a result of her early training and discipline in classical dance and dramatic technique in England; yet her actual method seemed much more closely aligned to the playful and emotive practice of mid-20th century America. In a Globe and Mail article from 1959, she is quoted as saying: “One day one of my young pupils asked me if I had ever read Stanislavsky. ‘Who?’ I asked. ‘You know. Stanislavsky. The Method.’ I’d never thought of it before but, you know, I suppose I must use The Method – but it’s just the way I feel I should teach’” (Johnson).

Fundamentally though, her small-M method could perhaps be described as rooted in concepts of self-esteem, fairness, and collective success. She remarked: “A big, annual production is bad for the morale of those students who get left out of it – everyone gets a chance with weekly performances” (Wells). She was never aloof to the dilemma of fostering inclusiveness within what might be seen as an essentially extroverted and individualistic competitive study: “We shake them up together,” she said of her students, “and somehow they come out alright” (Johnson).

Marjorie Purvey’s School of Life

By Maria Meindl

Marjorie Purvey was my party story – at least, one of them. She featured prominently the yarn called My Dismal Acting Career.

“Open your EYES, dear!” I would exclaim, imitating her tone of utter exasperation. “You are Alice, just arrived in Wonderland! Look around you; it’s a marvellous place!”

At age seven, I didn’t do wonder.

“Ahhhnd …”

Channelling Miss Purvey and her way of embellishing each lowly conjunction with a sweep of her arm, I would introduce another anecdote with a segue along the lines of: “It only went downhill from there.”

Funny stories, yes. But they contained a seed of pain. My overriding memory of the Toronto School of Acting was of feeling like a failure. I remember walking around the walls during the few months I studied there in the late 1960s. Here were signed photographs of children – not just looking successful but successfully looking – with that elusive sense of wonder – into the upper corners of their frames. I was a shy, anxious kid, and we were having a tough year in our household. My parents – who were both trained as performers – assumed I needed my own moment on stage. As it turned out, it was the single place on earth where I felt most utterly wrong.

Stories aside, I never blamed Miss Purvey. She was right about a lot of things. My personality began to change when I got glasses and discovered the brave new world beyond the curtain of hair in front of my face. Ahhhnd, that flourish of the hand taught me something, too. Transitions deserve attention. On the stage, on the page, and in life.

My parents were right, too, about prescribing theatre as an antidote to my troubles; they just got the dose wrong. Ever since, I’ve hovered somewhere in the vicinity of performance, with a profound admiration for anyone who actually steps on stage. Years later, as a PhD student, I came to meet Martin Julien, and – somehow – we fell into conversation about Marjorie. He shared a fragment of his writing with me. The steps going up from Yonge Street … the raised platform … the pictures on the walls: it all came back. In my research and writing, I had long been interested in the possibilities of doing oral history interviews in groups, but never had I sensed the visceral power of memories coming together like shards of a broken plate. Memory, it seemed, offered a sense of connection the classes never had.

Over the months that followed we had conversations with just a few of the many students who had studied at the Toronto School of Drama. Frank DeFrancesco, Catherine Hayos, Suzanne Hersh and Gerald Isaac met over zoom, in groups or alone, to talk about Marjorie Purvey. Martin Julien’s research has unearthed evidence of the scope of Purvey’s career. Her influence was immense, not just among professional actors, but among many children like me, trying to learn something about ourselves and how we fit into the world.

Gerald Isaac who continues to draw inspiration from his time with Marjorie Purvey – not just in his performance work, but in running his own independent studio – has shared materials from his personal archive.

[click on an image to enlarge]

Hawkeye and the Last of the Mohicans

One of Miss Purvey’s roles was that of Martha Wales in an episode of Hawkeye and the Last of the Mohicans, a Canadian-made Western series based on the James Fenimore Cooper novels. This is a classic “cowboys and Indians” tale, in which the former are depicted as peacemakers, the latter, as simultaneously incompetent and dangerous. They are also played by white actors. Purvey’s starring episode was titled “The Search.” The content and aesthetics are deeply

troubling, with obvious and chilling reference to the John Wayne/John Ford movie The Searchers, from 1956. The plot was practically lifted wholesale from this wholly disturbing Hollywood “settler” film. With terrible irony, it tells the story of a white child kidnapped by a “Medicine Man” and raised to forget he is white.

The episode is in black and white, and that makes it easy to think of it as dated, a bad “chapter” in Canadian cultural history, but these stories continue to be played out today, in systems of incarceration and in the overwhelming representation of Indigenous children in the child “welfare” system (Edwards). The 2009 documentary Reel Injun explores the real-life consequences of the way Indigenous peoples have been mythologized in Westerns, as well as their own contributions to cinema, going back to the silent era (00:19:00-00:00:22:00). In addition to being used as both an excuse and a coverup for ongoing land-theft and genocide (00:10:16-00:00:14:45) the dehumanizing tropes of Westerns have been internalized by generations of children (00:38:00-00:42:15). As MHA (Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara) Nation scholar Michael Yellow Bird writes, “Cowboys and Indians are this nation’s most passionate, embedded form of hate talk” (42).

Indigenous artists still struggle to have their own voices heard, while their stories are told by others. As part of a panel discussion almost a decade after the launch of Reel Injun, Nehiyaw and Jewish film-maker Ariel Smith stated, “There’s a very deep-seated, long history of a great deal of entitlement felt by non-Indigenous people to Indigenous people’s bodies, stories, experiences … entitlement to the land, entitlement to everything …” (00:05:00-00:5:45).

Works Cited

Chamberlain, Frank. “Radio Column.” The Globe and Mail. May 15, 1945. 11.

Diamond, Neil, Catherine Bainbridge, Jeremiah Hayes. Reel Injun. National Film Board of Canada, 2017, OverDrive. https://www.overdrive.com/search?q=reel+injun&f-formatClassification=

Edwards, Kyle. “How First Nations Are Fighting Back against the Foster Care System.” Macleans.Ca, www.macleans.ca/first-nations-fighting-foster-care/. Accessed 17 Sept. 2021.

“Film Fame May Be Near But Lad, 12, Undisturbed”. ----- The Toronto Star.

Haworth, Eric. “The flexible whirl of child actors,” The Globe and Mail. Jun 10, 1965. W1.

Johnson, Brian D. “Hollywood’s Shocking Reel Indians.” Macleans.Ca, 24 Feb. 2010, www.macleans.ca/culture/hollywoods-shocking-reel-indians/.

Johnson, Kenneth. “Miss Purvey has been shaking them up for fifteen years”. The Globe and Mail. Jul 18, 1959. A14. Nothof, Anne. “Amos, Janet”. www.canadiantheatre.com/dict.pl?term=Amos%2C%20Janet. Retrieved Dec 4, 2015.

“Rochelle Goldstein.” www. http://johnhart.tripod.com/rochelle.html. Retrieved Dec. 9, 2015.

TIFF Talks. Reel Injun with Ariel Smith, Melanie Hadley, and Cowboy Smithx | AABIZIINGWASHI. 2017. YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A8CE0S45A2E.

Wells, Lana. “Drama’s many masks can be therapeutic.” The Toronto Star. Nov 9, 1966. 65.

Whittaker, Herbert. “Show Business.” The Globe and Mail. Oct 12, 1951. 24.

Yellow Bird, Michael. “Cowboys and Indians: Toys of Genocide, Icons of Colonialism.” Wicazo Sa Review, vol. 19, no. 2, 2004, pp. 33–48. JSTOR, doi.org/10.1353/wic.2004.0013.

Endnotes

1 . My one unforgettable triumph was the day Miss Purvey cried during my performance of Mio’s famous third act speech from Anderson’s Winterset (1935): “…I came here seeking/light in darkness, running from the dawn/and stumbled on a morning”.