Written by Kelsey Jacobson

Where is the audience in theatre and performance archives? What is their role in archival practice? My research as related to the Gatherings project is concerned with the ways in which audiences and spectators create and maintain their memories of the productions they attend, what those collections--those archives--reveal about their relationship with performance, and the extent to which audience members are included or excluded in current and future archives. Audiences are a fundamental part of the theatrical or performance event, but their presence can be difficult to find in archival materials that may privilege actors or performers, production details, and so-called “official” accounts.

Kelsey Jacobson’s ‘unofficial’ archive of audience experiences: a bulletin board in her room with ticket stubs, programs, and other ephemera pinned to it. Inevitably, the most recent experiences are layered on top.

Rather than seeking to find the audience in pre-existing archives, then, I decided to speak to audiences themselves to understand how best the audience may be invited into the archive as creators, spectators, historical witnesses, and curators. How might the necessary multiplicity of perspectives of audience members and inclusion of broader communities productively reshape the hierarchies and interrogate the accessibility of archives? If audiences themselves are amateur archivists--taking photos, preserving tickets and playbills, creating Tweets or posts about the show and their response--to what archive do these materials belong? What might non-expert audience methods of archiving reveal?

Image of Barbara Moore’s notebook documenting her record of plays, organized alphabetically per page.

From February to July 2020, I interviewed eight audience members – Kit Moore, Barbara Moore, Don Kendal, Francie Kendal, Shirley Davis, Sandy Moser, Janis La Couvée, and Vera Kadar - who were living variously across the lands we now call Canada. I sought these people out through leveraging my personal networks: the only requirement for participation was that I was interested in speaking with people who had seen a lot of theatre but were themselves not professionally involved in theatre-making. In my interviews, I began by asking each interviewee to describe some of their most poignant theatre memories. Their theatre-going histories were deeply impressive: some had seen upwards of 1000 plays, some had been dedicated subscribers of particular theatre companies for decades, some had sat on numerous award committees and juries, and one had been such a fan of a specific production of Angels in America that they volunteered to usher it twenty-one times out of the production’s entire 105-show run. I became fascinated with the question of how these dedicated audience members were tracking and archiving their own experiences. How had they selected what to describe to me? Did they keep records of their theatre-going? How do audiences curate their own archives and what insight might such processes offer to other performance archivists, historians, and theatre scholars?

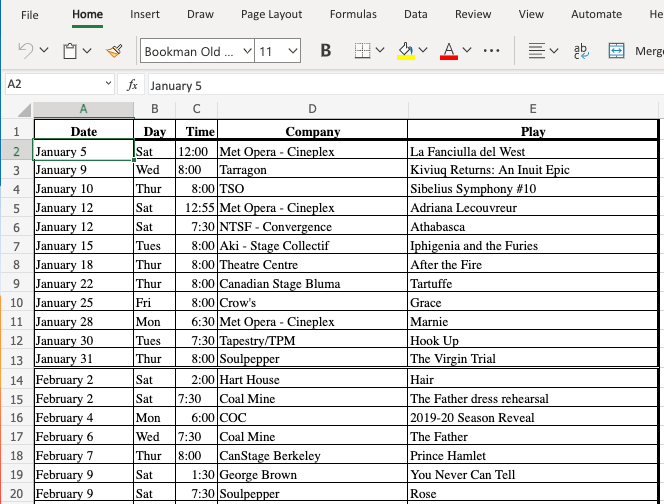

Don Kendal’s record of his volunteer ushering housed on an Excel spreadsheet, organized by date with record of the date, time, company, and play.

Each of the audience members I interviewed had impressive personal theatre archives, some of which are pictured here. For some, these “archives” were entirely without documentation, but for many they resembled material archival practice: Janis La Couvée created a blog that eventually housed over 800 reviews of performances, Don Kendal maintains an Excel spreadsheet detailing his volunteer ushering, Vera Kadar has a significant collection of playbills, Barbara Moore keeps all her ticket stubs as well as a notebook with brief entries, Shirley Davis has a wall of photos in her home based on productions and actors she has supported, Francie Kendal keeps programs (organized initially by theatre company but in subsequent re-cataloguing by year and alphabetical order), and Sandy Moser has an ongoing computer document that stores brief details of each of the 973 shows she has attended over the past nine years.

Janis La Couvée’s popular blog houses hundreds of reviews of performances from fringe and community events to professional productions.

Each of these personal archives reveals something of the audience member: their preferences, their values, and their interests. As Kit Moore described, he is drawn to shows that “capture my attention, and I just don’t think of anything else. It’s like meditation, it’s just all you’re thinking about is this play and you sometimes feel that you’re a part of the play: those are the ones I remember.” Francie Kendal described being drawn to shows that were intimate and felt “close.” Barbara Moore described an admiration for performances that feature strong, subtle performances. Shirley Davis offered her love of musicals and what she described as entertaining theatre. None of their personal recollections are therefore what we might consider to be “complete” or “neutral.” Archives are, after all, always limited. They tend to hold material that is removed from the direct effect of the event in a way that mirrors human memory: fragmented and subjective.1 What the limited nature of these audience interviews and audience archives might do, then, is help to maintain an awareness of the limitations and framing of archives in general. This is perhaps both a more challenging, but simultaneously more ethical approach to archiving: it performs the limitations of the project of understanding performance through archival fragments and trying to understand an ephemeral, live, emotive object through its remains.

Why include the audience in archival practice? It feels impractical to capture the response of every audience member (and indeed selectivity is a key component of research and archiving) and yet the preservation of non-expert, non-insider reports may help illuminate the complexity of live performance. Audiences are invariably composed of a multitude of individuals who may respond differently, or remember differently. This doesn’t challenge accuracy so much as offer insight into how audiences come to understand what they view and the many possible ‘methods’ of archival practice.

footnotes

Auslander, Philip. Performing Glam Rock: Gender and Theatricality in Popular Music. U of Michigan P, 2006. 96-7.