How to Stitch your Chapbook

BY THE EDITORIAL TEAM

If you have received your copy of our chapbook 'unstitched,' it's for a reason. We think it's valuable to be involved in the creation of a book. It reminds us of the book's physicality, the creative process, the importance of the dissemination of our work, its ephemerality as an object, its hand-made qualities. See below for further information about the origin of this idea, for us, in Eloísa Cartonera.

Also, it's fun. We have had stitching parties in the past, in person, including contributors and friends and family, and children of all ages. And we will have them again. But just for now, in these pandemic times, we are sending our orders 'unbound' and ready for stitching. Most of you don't need our help with that, and there are many ways to stitch. We are available to help if you want it. And we'll also say--it's all right if you leave your Gatherings Chapbook as you receive it, collated and folded and inserted into its hand-printed cover. The unbound book is still a book, and we think it holds together very well! But it holds together even better when it's stitched.

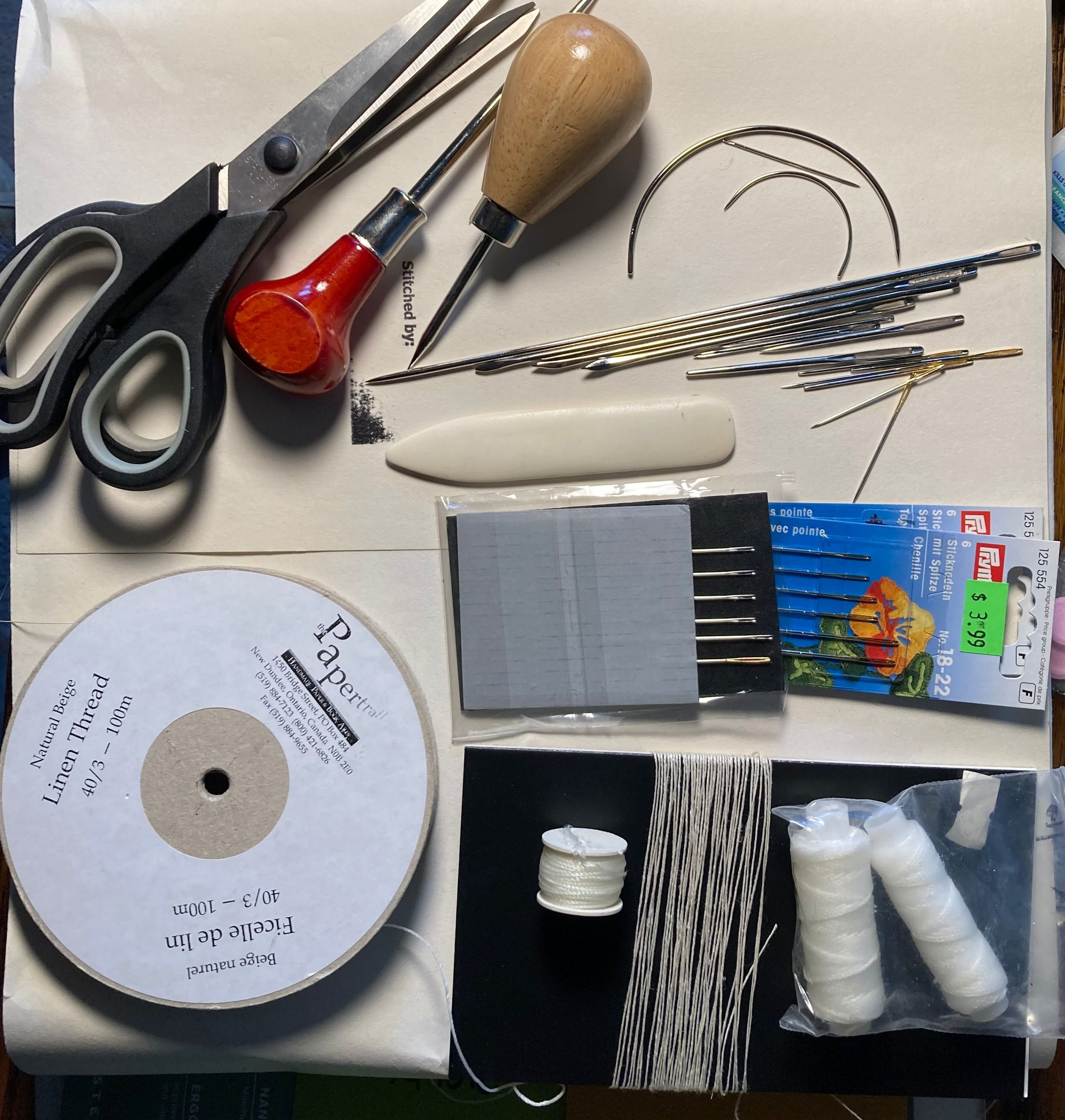

A collection of book-binding materials: a spool of thread, needles, scissors, and tools for creasing and punching paper.

Instructions for Stitching

First of all, we suggest you practice stitching first, with some sheets of paper stacked together before stitching your chapbook.

You will need a needle and thread. Any will do the job, though a thicker thread and larger needle would be better.

In your home, find an 'awl'--or any sharp pointed object, a nail or knife. Use this to create two holes along the spine of the volume. Measuring the length into thirds to make the holes provides good stability.

Place the volume inside the cover, centered. You won't need to put holes in the cover.

With these holes in place, measure a long length of thread and thread a needle.

From the inside, push the needle through one hole and through the cover.

From the outside, push the needs through the cover and the other holes you've made.

Tie the thread on the inside of the middle fold of the chapbook.

If this seems simple, it is. It just needs to be a strong thread, and a good tie.

Of course, you can change this. You can choose to have more than two holes--three holes, two sets of two holes, and so on. You can use different coloured threads, or string, or cord, or ribbon. You can creatively decorate your volume in any way you want.

And when you're done, there is a place on the inside back cover for you to record the date this chapbook was stitched together, and the name of the person who stitched it (so: Stitched by Jenn Cole on 18 November 2022). After all, we all deal with archives in the Gatherings Project. We all want to know the history of the document. Provenance!

We know that you'll enjoy stitching your copy of this work. And we know you'll enjoy the work it contains!

Why Stitch:

BY JIMENA ORTUZAR

It was Natalie Alvarez who thought we could all stitch the chapbooks collectively for our 2019 collection. The idea came from an Argentinian cooperative, Eloísa Cartonera, that I wrote about in the edited collection Sustainable Tools for Precarious Times (Palgrave Macmillan, 2019; edited by Alvarez, Claudette Lauzon, Karen Zaiontz).

Eloísa Cartonera is a small independent press founded in 2003 that produces inexpensive books made by hand from the cardboard collected by cartoneros (cardboard pickers) who emerged in the wake of a brutal economic and political crisis in Argentina. The cartonera engages the cartonero community at large through the purchase of cardboard, offering cartoneros a higher price that recycling factories pay. The press operates as a workshop open to the local community and a growing public that participates in the book-making process. Available on site as well as in bookstores and cafes, street stands and book fairs, the low-priced books make literature accessible to those unable to afford the escalated prices of the publishing conglomerates.

The small press describes itself as ‘a social and artistic project in which we learn to work together in a cooperative manner’ in line with the open spaces of collective activity that formed in the rubble of fiscal collapse. The experience of working together in a collective space becomes as important as the book. As its own slogan proclaims, Eloísa Cartonera is ‘Mucho mas que libros’ (Much more than books!), pointing to the live act of collective creation that extends the field of publishing into that of performance.

The books produced are thus not just cardboard books; they are libros cartoneros (cartonero books) that in addition to the written text, carry traces of their collective production. If mass-produced books guarantee the precedence of the literary work over its copy through the uniformity of the print edition, cartonero books call attention to their own material emergence – their rough edges and textures constantly pointing to the cartoneros and the collaborative creativity that follows from the recovery of waste. The materiality of the book is thus a reminder that the point of the cartonera as an editorial project is more about incorporating the labour of the cartoneros in the creative process than it is about their representation. Nevertheless, in assuming the name ‘cartonera,’ the project sutured its identity to that of the cartoneros on whose labour it depends. And as this editorial concept transmigrates northwards – there are now more than 60 cartoneras in over 20 countries – the ‘cartonera’ designation remains and with it the figure of the cartonero.

What makes Eloísa Cartonera significant as an instance of cultural agency is that the project is one of the few responses to the post-crisis turmoil that continues to be self-sustainable. The independent press refuses financial donations, grants or subsidies, and relies solely on the alternative market it creates for vanguard literature. This is possible not only because its costs are low but also because it is based on the idea of copyleft in which writers give permission to have their work published rather than sell a copyright to the publisher. Both established and emerging writers have donated to the project. The cooperative, in turn, has reintroduced Latin American authors omitted by transnational publishing companies while making visible a new generation of young Argentine authors. In doing so it responds to the commercialization of literature by the publishing conglomerates that formed in the 1990s as a result of neoliberal doctrine and began to influence literary taste. Eloísa’s intervention into the literary field opens up a space to (re)discover old and new literature by making it accessible and affordable.

Hence poet Edgar Altamiro’s moniker for the cartoneras: ‘disidentes del ISBN’ (dissidents of ISBN).