On Tuesday, 6 December 2022, at 11am ET, Stephen Johnson talked with Marlis Schweitzer about her first experiences with Performance--her 'First Gatherings.' A recording of that conversation is included below, in full, along with a transcript. Marlis teaches in the Department of Theatre and Performance at York University, and researches and writes about the history of performance. You can find out more about her life and career here.

Marlis grew up in Kelowna and Victoria, British Columbia in the 1980s. Her first memory of attending a theatrical performance was a Christmas Pantomime in Kelowna when she was about six years old, vivid not only because it was a special event with her mother, and because she was given a 'key' to hold that figured in the plot of the play, but also because it was a performance space that she herself would perform at just a few months later with her ballet class.

As she remembers, with accuracy and detail, she grew up surrounded by performance of every kind. She remembers the Kaleidoscope Theatre, an important children's theatre company, performing at her school in Kelowna. She remembers the deep impression performances in the early classroom had on her, including a full circus in Kindergarten, and a (somewhat more unsettling) rendition of the Three Billy Goats Gruff. She talks about the importance of the many varieties of performance cultures that surrounded her as she grew up in these two cities, including ballet lessons when she was young, singing lessons in her teens, as well as church choirs, operatic societies, baseball, video rentals from Blockbuster, and watching The Sound of Music on television.

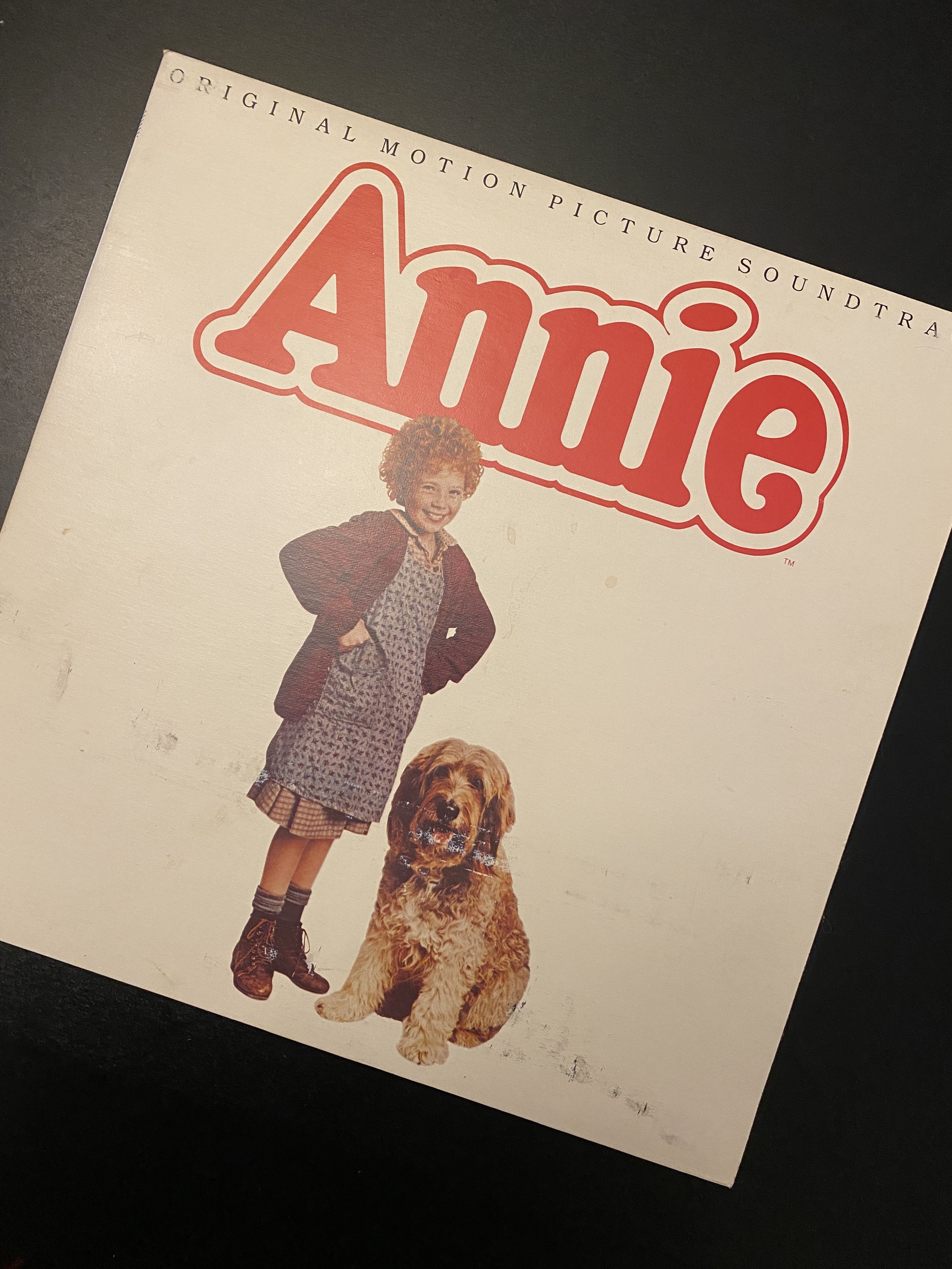

There were clear, life-changing events in Marlis's relationship with performance. She describes a production of the musical Annie, co-created with friends in her neighbour's basement, a true 'home theatrical,' with costumes, props, and an audience. This 'production' was not based on a script, or a filmed version (which came out in 1983), but on her friend's memory of seeing a live production in Vancouver, on the material objects and souvenirs available from that show, and on the cast recording--it was a rendering of a performance from archival and oral histories. Later, in her mid-teens, she was cast as Maria in West Side Story, a significant experience for her as a teenager in a culture of high school students, acting and singing the role of a teenager, where art and life commingled. In both cases--Annie and the ten-year old, Maria and the sixteen-year-old, the impact of the work of art resonated with the performer.

Marlis didn't take any arts courses in high school, but she grew up in a world surrounded with the opportunity to perform and to witness performance. In her later teens, she appeared in a production of The Sound of Music for the Victoria Operatic Society, and from there made her way to the University of Victoria to study Theatre and History. She has been studying both of these subjects ever since.

And Archivists take note--Marlis kept meticulous scrapbooks during these years.

TRANSCRIPT

[00:00:06.010] - Marlis Schweitzer

Hello. My name is Marlis Schweitzer. I live in Toronto, or Tkaronto, but I was born in Kelowna, British Columbia, and I am currently a theater professor at York University in the Department of Theater and Performance. I see myself as a theater and performance historian. I was trained at the University of Toronto, where I received my PhD. I had the wonderful opportunity, Stephen, of working with you as my supervisor. And I love all aspects of theater performance history, particularly looking at the history of performance, actors and actresses, as well as the connection to material culture. So objects, all kinds of objects, costumes, props, set pieces, ephemera, collectibles, all of that is something that I have been obsessed with for many years. And it's something now that I can call 'work.' So that's a little bit about me. I'm on sabbatical. I've just come off of four years as a department chair. So I'm really delighting in research again.

[00:01:20.170] - Stephen Johnson

That's great. That's exactly what we needed to know. And where did you grow up? Because a lot of this has to do with early experiences of theater that I'm going to ask you.

[00:01:34.860] - Marlis Schweitzer

Sure, sure. So I was born in Kelowna, BC. And lived there until I was about, I think, grade three, where we moved to Edmonton for a very short period of time, and then we moved back to Kelowna and then stayed there until I was in grade five. Then I was in Victoria. I know we did a lot of moving around. Then I moved to Victoria, BC, where I stayed basically from grade five all the way through my undergraduate education. Once I was in Victoria--a little bit of old England--things stabilized, but my earliest years of theatre going and performance training happened in Kelowna.

[00:02:18.510] - Stephen Johnson

Right. Well, then that leads to my first question and in other interviews, other discussions that I've had, we've certainly ranged widely from the very first experience, but I wonder if we could just begin there. What's your first memory of attending something that you would define now or define then as theater or performance of some kind?

[00:02:45.830] - Marlis Schweitzer

So one of my earliest memories of attending the theater was the Christmas pantomime in Kelowna. And I don't actually remember how old I was. I was probably, I want to say six. And it was a really special evening because it was just me and my mom, and my mom was so good to have special sorts of little outings--with my brothers as well--so everybody had like alone time or special time with mom. But I just remember being able to get dressed up as really something. I don't remember what it was, but just the feeling of being in a nice dress. And then the thing I loved, which perhaps is where my obsession with objects begins, was that as part of the pantomime, we received this large key, like a key that you could put into a doll to wind up, like a wind up toy.

[00:03:38.620] - Stephen Johnson

Right.

[00:03:39.320] - Marlis Schweitzer

And it was covered in like, in tinsel paper. And at various moments, as with Pantomime performance, I didn't know at the time, but of course I now understand this, the whole audience interaction component. We had to raise up our key and do whatever we were instructed to do to help the hero or heroine and vanquish the villain. And there was just something about having that key and then being able to take it home with me that was so special as a kind of part of the performance and also then a memento of the performance. So that's one of my very earliest theater going outings.

[00:04:14.130] - Stephen Johnson

That's fascinating and very interesting that you'd remember the object. That does say a lot about you.

[00:04:21.280] - Marlis Schweitzer

It does. I know.

[00:04:23.170] - Stephen Johnson

Do you remember the space?

[00:04:28.290] - Marlis Schweitzer

I kind of have a memory of sort of where relative to the stage, we were sitting, like, we weren't sitting in the front row. It was kind of like the middle of the auditorium. I know it was sort of downtown Kelowna-ish. So it must have been one of the older theater buildings there. Later on, when I was growing up in Victoria, I'd get to see real fancy theaters. This wasn't a fancy theater in my recollection. More like a sort of more civic auditorium-esque, I think.

[00:05:06.610] - Stephen Johnson

Would have been a more recent build--like a more recent building, probably. It was built for the community, sort of centennial funding and that sort of thing.

[00:05:17.740] - Marlis Schweitzer

Late. That makes a lot of sense. Yeah, probably like 60s, early 70s, because I would have been going to this like late 70s, early 80s. But I don't have any more vivid memories. I do remember being in a space surrounded by other people and that kind of excitement, feeling that energy.

[00:05:38.220] - Stephen Johnson

And how does that fit in with the other things that you would have done that were public or performance oriented, surrounding that? Had you been in spaces with large groups of people, had you been in spaces with small groups of people, had you been in spaces that had some kind of raised area at the front, whatever that would be?

[00:06:07.980] - Marlis Schweitzer

Right. So I had different kinds of experiences. We went to church, so there was certainly the church experience at that time. I don't actually remember--one of my experiences as a young person was moving churches very often. So I don't actually have a vivid memory of what church we were going to at that time, if we were going to one at all. Various disagreements with various, I don't know, belief systems, but that would have been one. And then also experiences at school and then even with my friends. So if this was around kindergarten, which I think it must have been, I had an amazing kindergarten teacher who helped us stage an entire circus performance. And so this is more of a memory of the circus where we were in the gym, and we all got to have our little costumes and play, I think. I know I had orange, orange, basically, like bodysuit/bathing suit, and I got to have my hair up and was doing things on, like, the monkey bars, basically, 'look at me flip.' But there were some of my friends who were lions. And so that was an experience, a kind of in-the-round circus experience.

[00:07:22.090] - Marlis Schweitzer

Then I also remember earlier, I think one of my earliest memories of performance is actually a more dramatic one, where in a preschool, we had to re-enact the story of the Three Billy Goats Gruff, and I had to play one of the billy goats crossing, and then there was, like, the troll right under the bridge. And that was terrifying. That was just the thought of crossing, and then my teacher was like, okay, well, do you want to be the troll instead? And that was slightly better because I guess it was about controlling when I came out. But I can't say that that was the best experience of performance. I've had experiences of it in school, in preschool, and it wasn't until I was a little bit older that my friends and I put on our own basement production of Annie the Musical. But we can get there.

[00:08:14.510] - Stephen Johnson

We can get to that, and we will. That's great. But that's very interesting that you had these other experiences, and you do remember these other experiences. You remember the negative repercussions of having trolls underneath the bridge. I have similar, you know, memories of kindergarten and reenacting these things. And I remember thinking many, many years later, why did they--did they not know that this was going to frighten us? But maybe that was the point. But yes, acting that out is interesting. And the other things you mentioned as well. Did any of those things--not that you're going to make a connection when you go in and see these things--but I'm making an assumption here, which maybe I shouldn't, that the great difference was that you went into a separate space, and there was this space that was there, that was unusually, for a very particular purpose. And then you saw this pantomime.

[00:09:22.770] - Marlis Schweitzer

Yes, definitely. The whole experience of it just getting to go, having the time alone, like, without my little brothers being able to go into this space was a special event, and then having the 'accoutrements' or the toys and the props that were part of it, and then being invited then into that space. So, yeah, all of that was really exciting. And I'm trying to remember if there--because I started ballet around the same time, like ballet classes--and I don't know if there was any connection between the pantomime and the ballet. There may have been. Actually, you know, what? Now that I remember, I think it was the same auditorium where we did our ballet recitals. And that was something I remember, really with great excitement because of the whole--again, a much more positive experience of performance--because we'd been rehearsing for many months. But I believe that must have been the same auditorium.

[00:10:25.350] - Stephen Johnson

And would that have been a little later than the Pantomime or the same--would you have been in the auditorium?

[00:10:33.330] - Marlis Schweitzer

Prior to. I don't think I would have been, no. I think that was my first experience of it. But it probably makes sense that then if that was Christmas, I think our recital may have been in the spring.

[00:10:46.830] - Stephen Johnson

So you were occupying the same space as the Panto in short order.

[00:10:50.830] - Marlis Schweitzer

There we go. I want to be on that stage.

[00:10:53.830] - Stephen Johnson

That's right. Wow. Thank you for that. That's very interesting. And honestly, it connects with so many other people I've talked with about the things that you remember.

[00:11:09.650] - Marlis Schweitzer

Another thing I just remember, too, which is around the same time, is because we lived in BC, there was early Kaleidoscope theater. I don't know if you know Kaleidoscope Theater. They're based in Victoria, but they also did a lot of touring of schools. And I remember that they came to our school. It may have been, like, Grade One or Grade Two, and they came through and did, I think it was an Inuit story. And I remember that was quite exciting to have your gymnasium transformed into a theater space. So that's an early theater memory.

[00:11:46.770] - Stephen Johnson

So quite a bit of theater, in fact, or quite a bit of performance between you yourself, performing ballet class in front of other people and also hiding--being attacked by trolls and all the other things. You're also attending a standalone production where you are in the audience, and that was a big deal. So I guess from there, we do move on to Annie. Was there something intervening between that and...?

[00:12:16.320] - Marlis Schweitzer

Annie is, like, the most consequential theatrical event of my young years. Do you want me to just tell you about it?

[00:12:27.380] - Stephen Johnson

Please, I would.

[00:12:29.230] - Marlis Schweitzer

So, my very best friend, Jennifer Lefontaine, came home from a visit to, I believe it was Vancouver, and she was telling me and our other friends, we all lived on the same block in Kelowna, about this show that she'd just seen in Vancouver, Annie, and we were like, wow, this sounds amazing. And it was just before the movie had come out as well. The movie came out, I believe, in 83, so this was probably 82 and the musical version. And so we were kind of soon obsessed with Annie. I had the tape with the cast recording, and my friend Jen and I would sit at her kitchen table and then just come up with an entire list of all the Annie products we wanted. So we wanted, like, Annie pencils and Annie notepads and Annie purses and Annie dolls. And it was like anything that we could think of, Annie berets, we wanted them. And of course, the biggest was, like, the Annie locket, because that's an important object in the film that connects her to her parents. So we wanted some variation of that. And I didn't get the cool one, which is like, the actual necklace, but I got a one with a little doll in, it's like a plastic doll in a little heart.

[00:13:39.640] - Marlis Schweitzer

Anyway, so we were obsessed. So then we're like, well, what if we do our own basement production of Annie? And so we began. We're like, yeah, of course we can do that. And my friend Jen had this great kind of fully semi-furnished basement. And so we got our friends together. We even enlisted my younger brother to play the dog and to play all of the male characters. So he played the character of Rooster, who's connected to the kind of flighty Lily. And did he play Daddy Warbucks? I don't think he did. But my friend Jen got to play Annie, and I got to play Molly, the orphan friend of Annie, Miss Hannigan, who runs the orphanage, and Grace, who is basically the assistant to Oliver, to Daddy Warbucks. So I played all the secondary, really good, juicy roles. And then our other friends I know, like, triple casting. And they were the orphans and then the other characters. And what I remember, one of the most vivid memories is there's a song called 'We'd Like to thank You, Herbert Hoover.' And we did not know who Herbert Hoover was or what the significance of this song was.

[00:15:00.910] - Marlis Schweitzer

Of course. It's like this ironic song about basically like, screw you, Herbert Hoover, for your terrible treatment of the poor. And we were singing along to the cast recording, and I remember my dad in the audience when we performed it for our parents, saying, 'Sing Louder.' And we'd say, 'Dad, we don't know the lyrics!' That moment was just prime performance.

[00:15:28.930] - Stephen Johnson

And this was a performance in the basement.

[00:15:31.870] - Marlis Schweitzer

In the basement, yes.

[00:15:33.480] - Stephen Johnson

And you still got heckled.

[00:15:36.250] - Marlis Schweitzer

I know. I think it's my dad's Lutheran upbringing or something. I don't know. Yeah. I don't know how long we rehearsed. It felt like weeks, but it was probably only days. And the costumes, of course, that was really exciting.

[00:15:54.590] - Stephen Johnson

That's fantastic. And it must have been quite a bit of, I mean, you had an audience in the basement. How many people would have been in that audience? Like, half a dozen? More?

[00:16:04.920] - Marlis Schweitzer

Yeah. Maybe eight sets of parents. And maybe a brother or sister--

[00:16:07.260] - Stephen Johnson

Of course. No, that's legit theater. Home theatricals. A long tradition of that.

[00:16:18.590] - Marlis Schweitzer

Nineteenth Century. Absolutely.

[00:16:23.450] - Stephen Johnson

Well, that's very interesting. And the fact that it would all come to your home through--I mean, it's a Broadway musical!

[00:16:33.850] - Marlis Schweitzer

Exactly. And I still have so much. Again, back to objects. I still have so many of the things that we purchased and obsessed over at that time. It's like early fan culture, celebrity culture, and then just the material culture of performance. And I have, like, the Annie record and so many of those things that were really formative just in my whole relationship to yeah, to theater, to commercial theater, to Broadway, to music.

[00:17:00.070] - Stephen Johnson

Yes, it travels well, that stuff. And you had a 33 1/3 record? You had a record? And were there other musicals surrounding that as a culture, or was it just Annie? All Annie all the time?

[00:17:15.800] - Marlis Schweitzer

It was like all Annie for at least a year. That was the real obsession.

[00:17:20.840] - Stephen Johnson

Well, I understand that, because that would be the show that would appeal to your age.

[00:17:28.370] - Marlis Schweitzer

I mean, there were like, things like Cabbage Patch Kids, but that was different.

[00:17:33.550] - Stephen Johnson

Certainly was different.

[00:17:36.270] - Marlis Schweitzer

But no, the musical obsession was definitely Annie.

[00:17:39.480] - Stephen Johnson

That's very interesting. And in terms of other kinds of performance besides that, you've given me some of the things you did. But if we just move on from there a little bit, when did you first yourself start becoming involved in school theatricals? And, I mean, you'd be a little older then, and some people don't get involved in school theatricals until way later. But you may have and I wonder if you could just talk about that a little bit, because all of this leads into your interest in doing theatre as well--

[00:18:14.980] - Marlis Schweitzer

Yeah, so I didn't take any drama classes in junior high or high school. For some reason. I'm like, no, that's not me. I don't really think I can do that. I don't know why. Then when I was in grade eleven, I started taking singing lessons, and then I really enjoyed that. I had a great singing teacher who was training at UVic in the music department, and then there were auditions for West Side Story, so I thought I'll go out for that. I had a friend who was also taking lessons with the same teacher, and she also decided, hey, why not? Let's audition. And I was very surprised and delighted when I was cast as Maria. Yeah, I was not expecting that. It was a bit terrifying because I just started the formal training and that is a very hard role to sing.

[00:19:17.540] - Stephen Johnson

And you would have been what age?

[00:19:19.250] - Marlis Schweitzer

I think I was 16, turning 17. So I did that and we got to perform at--not our own high school auditorium, but a different high school auditorium.

[00:19:33.120] - Stephen Johnson

And it was a school production. It was a high school production, but in an auditorium.

[00:19:38.750] - Marlis Schweitzer

Yeah.

[00:19:39.690] - Stephen Johnson

That's pretty--that's quite amazing. I mean, it's not amazing that you would be cast, of course, but you're right, that would certainly be a memorable effect in your life being Maria.

[00:19:53.090] - Marlis Schweitzer

It was, yeah. And I remember for the audition, for The Callback, we had to do some interpretive dance piece, and I remember I had very little. I did as I mentioned, I did ballet when I was much younger and I continued to do that a little bit till grade four or five and then sort of stopped. So I hadn't had any more formal training in dance. And so I did this. I'm sure it must have been the most cringy interpretive dance to the Brian Adams song Everything I Do, I Do It For You from the Robin Hood movie soundtrack. And I thought it was so beautiful. And thankfully, Maria doesn't have to do much dancing in West Side Story because I did not have the goods there. But, yeah, the Tony, he was great and I kind of had a super crush on him. But whatever. I think it helps.

[00:20:50.270] - Stephen Johnson

I'm sure it helps. The interpretation, chemistry.

[00:20:54.090] - Marlis Schweitzer

The Chemistry. Yes. And that was my very first kiss. I hadn't had a boyfriend or anything like that, so my very first kiss happened in the whole scene at the dance. So it was very meta. Very meta. Our first rehearsal and the first time we had to kiss, that was a little intimidating to be surrounded by the rest of the cast, and going 'I don't even know. What do I do? How do I do this?'

[00:21:17.270] - Stephen Johnson

Very interesting. And the whole way you tell it, I mean, the whole idea that it's not just about putting on a play, there's this whole thing going on, because it's a musical, as we have discussed in another setting, it's layered with traditional ways of performing things. On the other hand, it's a play about teenagers. And you're teenagers.

[00:21:46.130] - Marlis Schweitzer

I watched Natalie Wood--

[00:21:48.610] - Stephen Johnson

--and you could connect. So you are Natalie Wood. Well, you know, that's very interesting. And, you know, in terms of the singing and the performance of that, what was the other training surrounding that? I mean, it was a school musical and people do school musicals, but there are greater and lesser degrees to which a school invests in these musicals. And I wonder if you had anything to say about that context. Was there a real infrastructure or was it more informal?

[00:22:23.680] - Marlis Schweitzer

Well, we had a drama teacher there, a dance teacher and the music teacher. They were all involved. I think it was pretty stressful, especially for the music teacher. The drama teacher was kind of, I think, a self styled cool guy, as I think many drama teachers have been historically--would hang out with all the cool-- This is early Grunge, like 90s grunge, Seattle Sound, all of that stuff was really influencing high school culture. So most of the Jets had long, kind of Grungy hair. So there's an interesting look. But the drama teacher was like a motorcycle rider and he had this leather, so he brought that vibe to our rehearsal space. And then we had the dance and art teacher who was--I don't know how technically--but dhe was a really lovely, warm, kind of maternal presence. So it felt good. I think later on, I kind of look back and go, oh, I don't think they had necessarily the kind of training that I know some of the performing arts high schools in Toronto have. It was nothing of that level or even there's another school called Oak Bay where the kind of previous training and experience that the drama teachers had was much greater.

[00:23:46.570] - Marlis Schweitzer

But I didn't know any different. I was like, okay, this is cool. So I felt well supported. And then I had my own singing lessons on the side to tackle the really hard music.

[00:23:59.290] - Stephen Johnson

Right. And how about the costumes for that particular production? What would they have been like, and how carefully were they done?

[00:24:10.030] - Marlis Schweitzer

Well, my favorite costume was actually a dress that had belonged to my mom when she was, I think, in high school. And it was this beautiful sort of salmon pink dress, kind of 50s style, or maybe slightly sixties and spaghetti straps, lace bodice and full skirt. And I wore that--not for the dance at the gym, because that has to be a white dress. But I wore it in I think 'I Feel Pretty' in Act Two. And it was like, it made me feel so good. And so there was that. And then for the dance at the gym, where Maria has her white dress that she doesn't really like because it's a communion dress, they built that for me. And it was, looking back, not historically accurate. It was not a 1950s dress. It was a more, like, Laura Ashleyesque style, late 80s, early 90s, like, prom-esque dress. But it was really pretty. And there's little rosebuds all sewn on. So I liked that as well. But my favorite is the one from--

[00:25:22.870] - Stephen Johnson

Well, adding to the meta nature of the whole thing. Right?

[00:25:26.710] - Marlis Schweitzer

Definitely. And also, it's interesting because as part of that production, one of the negative consequences was that the woman or the girl playing Anita had just come back from Japan where she'd been modeling. And so I looked at her and she was, like, gorgeous and beautiful, and I thought, oh, I need to aspire to that. And so I basically kind of flirted with an eating disorder for about six months or more. And I lost a lot of weight, which is what allowed me to actually wear my mom's dress, because that still mingled in with that experience was both, like, the amazing love of theater and, oh, my gosh, I can do this, and that excitement. And then also, like, what do I need to do this? Oh, I just need to stop eating so I look better. So those two life experiences are pretty closely commingled.

[00:26:18.430] - Stephen Johnson

Boy, there's a lot to talk about there, but I don't know if you want to talk about that now. But when you started talking about how when you use the word meta, who would have thought that West Side Story would be the thing that would coalesce into all this cross fertilization, and would impress upon you in such a real way. Although it is high school and you are teenagers and that's all part and parcel of it. That's very interesting.

I want to go back to something you said because it jogs a memory of mine when I hear the word 'interpretive dance'-- that you auditioned. And this has to do with training. Not your training, but the kind of education you get in school. You didn't take drama in high school, but when you auditioned, part of the audition process for a role that had very little dance, really. One dance scene, but it's traditional dance. You had to do an interpretive dance scene. I just wonder if you have a sense, thinking back now of what it was that the people who did these things were after when they had people do that, because there's a lot of that that was done.

[00:27:51.400] - Stephen Johnson

And it would have been a time when these people would have come out of whatever training they had. And that training may have just been teachers college. It may not have been from school themselves. Although probably there was. I just wonder.

[00:28:07.690] - Marlis Schweitzer

Yeah. I have to assume, and I can't be sure, but I think there were separate callbacks for the Jet Girls and the Sharks. It was just me. And I think I came in to do some singing as well as some movement. So I think it was more they're just interested in seeing how I moved. And then it's kind of just more I don't know for sure. But my guess is that they said, pick a piece of music you like and just come and dance to it. Something just like that. Both--the two teachers were very free spirits. This is Victoria. Very kind of hippiesque. So I think their knowledge of that is like, yeah, just kind of move.

[00:28:48.870] - Stephen Johnson

And we both know now, after all these years, why. It's just they want to see whether you can. Whether you're willing to of course, there's that, too. Well, I'd like to go back a little and then forward a little. But going back a little because I keep trying to find the context surrounding--ever larger concentric circles of those first experiences in the theater. And you draw a line around it and draw a line around that. I mean, in terms of your witnessing of performance. Were you taken to the movies? Did you watch television? Did you listen to the radio? I'm guessing all of the above. But is there a sense of the context that sets you up for live performance? But it's close by.

[00:29:40.990] - Marlis Schweitzer

Yeah. Yes. All of the above. Didn't really go see--well, no, that's not true. We lived fairly close to a movie theater. So I'd go see stuff with my friends in the summer and that was kind of cool. My family was a big sports family. Both my brothers played baseball and so we spent a lot of time at the ballpark. And what else? Well, I do know that once I got into theater, then I started seeing a lot more theater and going to other high schools and their productions and things like that. So I kind of invested really intensely once I decided I was interested in that. But I always loved musicals. My mom would have us watch The Sound of Music. That was one of my favorites. And for a lot of those we'd go to Blockbuster, or wherever, and rent movie musicals. So that's like so many young people. My real entree into the history of theater other than Annie was through musicals, film musicals. And then I can't remember if we actually saw any live productions in Victoria. I don't think our economic standing at the time let us see a lot of that.

[00:30:56.870] - Marlis Schweitzer

But I did I forget to mention this. We went to a different church and the the minister from that church was from North Carolina and had come from a very different tradition of music and worship, I would say. And when I was like grade seven, eight, and I was in the choir and I loved it. It was an amazing experience for about a year. And we were there every Sunday. We'd have rehearsals once or twice a week and it was a kind of choir that doesn't just stand there. We actually had to, like, move and like, have the choreography. And I remember being assigned these, like, older ladies who I think at the time just seemed so ancient to me and going the wrong way. And it's like, no right, left. So that, I think, was also, in terms of performance experiences, a really important one.

[00:31:52.690] - Stephen Johnson

Absolutely. That's very interesting. And I'm glad that memory came back to you. Yeah. One of the reasons for asking these questions is, you have this great surround. I mean, you had this experience and I don't know what age you were when you were attending the church and singing in that choir, but I don't think that's a usual thing for people to be singing in a choir in a church where you moved. Choirs, maybe, but the one where you move, that's a special case.

[00:32:22.640] - Marlis Schweitzer

It was pretty radical.

[00:32:24.590] - Stephen Johnson

Very interesting.

[00:32:26.510] - Marlis Schweitzer

Yeah.

[00:32:27.230] - Stephen Johnson

And also, on the other hand, the relationship between you and Blockbuster and all of those musicals is also something that's common, I think, for a certain age group. Not really an age group. It crosses age groups. It's a bonding experience, as you've already said. I mean, with your mother, you'd watch these musicals. But to have the musical, being the important feature. I mean, you weren't going to Blockbuster and renting science fiction movies. [M: Well, my brothers were.] Well, your brothers were, but that's exactly my point.

[00:33:10.750] - Marlis Schweitzer

Yes. I was an avowed fan of WWF because of their influence, just like I influenced them with musicals. So they still enjoy the occasional musical and I still enjoy The Rock.

[00:33:26.210] - Stephen Johnson

Absolutely. No, that's also, thank you for mentioning. If I get through one of these interviews and nobody mentions wrestling, I'm disappointed. Really? That's fantastic. Absolutely. You watched WWF, which I remember watching when I was a kid. I didn't go live, but it was there on television. So you watched it. What role did it have in my life other than that? Well, it's amazing what you start...once the television invades the home. Boy, the numbers of things that you can watch that you otherwise wouldn't have had a clue even existed. And so it goes with musicals to some extent. And you mentioned baseball, too.

[00:34:11.060] - Marlis Schweitzer

Yes.

[00:34:11.570] - Stephen Johnson

And that's very interesting that you mentioned that, because to me, we all forget that sports surrounds us and that it is a performance idiom. I mean, you and I may not forget that, but we may forget it about ourselves. The fact that it's there and you're watching it and there's no question that it's a performance idiom. Some of my favorite live performances were the softball games down in the local park, watching the local guys competing, but mostly acting.

[00:34:50.490] - Marlis Schweitzer

Definitely. My dad was like a coach and yeah, that was a very strong part of my teen life, was my brothers' relationship to that sport and the good days and the bad days and how that could actually colour the whole family's experience. My younger brother was a pitcher. So all the highs and lows of that experience.

[00:35:15.330] - Stephen Johnson

That's very interesting.

[00:35:17.860] - Marlis Schweitzer

Yeah.

[00:35:20.310] - Stephen Johnson

I'm just going to go forward and then we'll be done. And then going forward is that you get through your teenage years, you start university, but you at some point turned toward theater studies. And at what point did that become clearly the way that you were going to tranfer? Yes. You said you didn't study it in high school. It didn't seem to be the thing. But then you did. So what did you study?

[00:35:52.910] - Marlis Schweitzer

Well, I did my first year at UVic--University of Victoria--and I did just a general first year. I did like, history classes, english, philosophy and so forth. And then I got involved in some community theater, and there was a great theater company called the Victoria Operatic Society or VOS. And I think maybe my Mom and I began to see some of their productions. They used to do three a year, like winter or fall and then a spring and sometimes a summer. And so I was like, okay, maybe they were going to do The Sound of Music. And so I auditioned for The Sound of Music and I got a roll of a Nun, a young postulate.

[00:36:43.230] - Marlis Schweitzer

That was actually a really wonderful experience because the director of that production was also one of the high school directors at this other school at Oak Bay, which had like a really good performing arts program. And I think I'd seen a couple of the Oak Bay's productions. I'd actually seen they did Romeo and Juliet, I think the year after we did West Side Story, somewhere around the same time I'd seen the Juliet, and I really liked that production. And then to come to Sound of Music, and I'm cast, and that's a great and exciting new opportunity outside of high school. And the Liesl I recognized was the Juliet from this Oak Bay production as well. And so she was like, just as I was, I think, 18, she was 17, something like that. And I kind of started to chat with her and get to know her. And it was around that time that I was chatting about, I was starting thinking, like, maybe I really like theater. I really like the experiences. I know we did some drama exercises, which I just remember this moment of being in whatever it was. Again, some interpretive dance movement, and kind of going like, oh, I really like this.

[00:38:02.470] - Marlis Schweitzer

And I recognized as well that my experience in high school and the training and what the teachers could offer was not at the level of what this other director was able to bring. And so there was something in that room, and I kind of even remember where I was standing in the room and kind of going, 'Hah, I think I really want to do this.' And so then I started to research at UVic, like, the theater department, and looked into that and, like, what is required? And I remember talking it was actually, I think, at a cast party to my friend (now my friend) Sarah, and she was also, she was just finishing high school, and she was like, oh, I don't know, should I apply to university? And I was like, yes, apply. Because if you get accepted, that's great, and if you decide not to go, you can still decide not to go, but if you don't apply, then you've already made your decision. And so, based on that, yes, I know--Well, I was I was a year older, you know, like, I was a very mature 18 year old.

[00:38:59.690] - Marlis Schweitzer

So in part because of that conversation, she did, in fact, apply and to the theater department, so I knew that there was one other person. And so, yeah, in my second year of university, I transferred to theater, and my friend Sarah, she's still my friend, and she's currently on Broadway.

[00:39:21.730] - Stephen Johnson

And what's she playing on Broadway?

[00:39:24.040] - Marlis Schweitzer

She's in the Tom Stoppard play, Leopoldstadt. And she's performed at Stratford. Sarah Topham is her name, she's performed all over the place. She's had tremendous success as an actor and I'm so proud of her. But it was in that moment of The Sound of Music where both I met her and I decided I wanted to really commit my life to theater. So I see it as a really important turning point in my life.

[00:39:50.240] - Stephen Johnson

Fantastic. And the fact that you know exactly the moment and pretty much where you were.

[00:39:55.790] - Marlis Schweitzer

Yeah.

[00:39:56.370] - Stephen Johnson

So you could take me to the spot.

[00:39:58.830] - Marlis Schweitzer

Exactly.

[00:39:59.620] - Stephen Johnson

This is where it all happened.

[00:40:02.510] - Marlis Schweitzer

Definitely. Yeah. No, I mean, the production was whatever it was, but I really enjoyed it. It was fun. And I was singing very high notes, like a high G, which was exciting.

[00:40:17.190] - Stephen Johnson

In fact, what you're telling me well, as we all know, you're surrounded by all sorts of performance, but that there also was a lot of opportunity for you. You didn't take it in the classroom, in coursework, in school, but there was a lot of opportunity in the community in various ways, for you to see theater and for you to perform in theater. And it's the performing in the theater that netted you the experience you needed to be able to major in it. Which wouldn't have happened if it was just the high school.

[00:40:54.740] - Marlis Schweitzer

Yeah. I would have just stayed in my history degree, and I ended up doing, like, doing a double degree, so BA and a BFA, which I had enough credits. So that was great. So I didn't have to give up the interest in theater, in history.

[00:41:09.440] - Stephen Johnson

Yeah. That's great. Well, you know, Marlis, you've been very generous with your time, and I think that I've gotten you through to a certain age now. I've gone through your entire life to a certain age. I could keep going, of course, but perhaps that's enough. Unless there were some things that you wanted to add that have come to you suddenly.

[00:41:34.010] - Marlis Schweitzer

No, I just think thank you for the opportunity to kind of travel down memory lane. And I think it's really fascinating that part of me is like, oh, look, it was right there at the start that my interest in material culture performance was there. Of course it wasn't, but I think about in high school, the meticulous scrapbooks I would keep of my experiences, and for the Victoria Operatic Society. So I had photographs I took, I had the programs, the tickets. I had other inspirations for different roles I played. And this was long before I knew anything about 19th century scrapbooking practices or other kinds of performance documentation. So when it came to doing grad school, it was like, oh, I kind of recognized a world that I'd already been kind of living in, in my home. So I still have those records. And that's really exciting to be able to go.

[00:42:29.310] - Stephen Johnson

I'm so glad that we continued that talk. I mean, the fact that you have that archive is unusual, extraordinary. I mean, it's not that people didn't keep scrapbooks, but to pay attention to them and to still have them, that's very interesting, because that also has to do with your interest in material culture.

[00:42:55.450] - Marlis Schweitzer

Yeah.

[00:42:56.200] - Stephen Johnson

Your interest in objects, because the scrapbook is an object.

[00:42:59.430] - Marlis Schweitzer

Yeah.

[00:43:00.070] - Stephen Johnson

And your interest in history.

[00:43:01.860] - Marlis Schweitzer

Yeah.

[00:43:03.750] - Stephen Johnson

So that's an important archive. You hang on to those.

[00:43:08.280] - Marlis Schweitzer

I will.

[00:43:09.850] - Stephen Johnson

No matter what people tell you. What are these doing here? No, they're important. That's very, very interesting. Thanks. And thank you for all of that. I really appreciate your talking with me.